System Failure: 7 Shocking Causes and How to Prevent Them

Ever felt the ground drop beneath you when a system fails? From power grids to software, system failure can strike anywhere, anytime—often with massive consequences. Let’s dive into what really happens when systems collapse and how we can stop them.

What Is a System Failure?

A system failure occurs when a network, machine, process, or organization stops functioning as intended, leading to disruptions, downtime, or catastrophic outcomes. These failures can be sudden or gradual, localized or widespread, and stem from technical flaws, human error, or environmental factors.

Defining System Failure in Modern Contexts

In engineering, a system is any interconnected set of components working toward a common goal—like a computer network, transportation grid, or healthcare delivery model. When one or more components fail to perform, the entire system may degrade or collapse. According to NASA’s Systems Engineering Handbook, a failure is “the termination of a system’s ability to perform a required function” (NASA SEH).

- System failure can be partial (degraded performance) or total (complete shutdown).

- Failures may be latent—hidden for years before triggering a crisis.

- Modern interdependence increases the risk of cascading failures.

Types of System Failures

Not all system failures are the same. They vary by cause, scope, and impact:

- Hardware Failure: Physical breakdowns like server crashes, circuit overloads, or mechanical wear.

- Software Failure: Bugs, memory leaks, or flawed algorithms causing crashes or data corruption.

- Human Error: Mistakes in operation, configuration, or decision-making.

- Environmental Failure: Natural disasters, power outages, or cyberattacks.

- Process Failure: Poor procedures, lack of redundancy, or flawed design.

“Failures are not random events; they are symptoms of deeper systemic flaws.” — Dr. Richard Cook, Resilience Engineering Expert

Common Causes of System Failure

Understanding the root causes of system failure is the first step toward prevention. While each incident has unique circumstances, research shows recurring patterns across industries.

Design Flaws and Poor Architecture

Many system failures originate in the design phase. Engineers may overlook edge cases, fail to account for scalability, or neglect redundancy. The 1986 Space Shuttle Challenger disaster, for example, was caused by a flawed O-ring design that failed in cold temperatures (NASA Rogers Commission Report).

- Lack of fault tolerance in system architecture.

- Over-reliance on single points of failure.

- Inadequate stress testing during development.

Software Bugs and Coding Errors

Even the most sophisticated software contains bugs. A single line of faulty code can trigger a system failure with global implications. In 2012, Knight Capital lost $440 million in 45 minutes due to a software deployment error that activated an old trading algorithm (SEC Report).

- Uncaught exceptions leading to crashes.

- Memory leaks degrading performance over time.

- Concurrency issues in multi-threaded systems.

Human Error and Operational Mistakes

Humans are often the weakest link. Misconfigurations, accidental deletions, or poor judgment under pressure can trigger system failure. In 2017, an Amazon S3 outage was caused by an engineer typing a command incorrectly, which took down thousands of websites.

- Lack of training or procedural oversight.

- Insufficient access controls.

- Failure to follow change management protocols.

System Failure in Critical Infrastructure

When critical systems fail, the consequences can be life-threatening. Power grids, water supplies, and transportation networks are all vulnerable to system failure.

Power Grid Collapse

Electricity grids are complex, interconnected systems where a single failure can cascade across regions. The 2003 Northeast Blackout affected 55 million people across the U.S. and Canada due to a software bug and inadequate monitoring.

- Overloaded transmission lines triggering automatic shutdowns.

- Lack of real-time data sharing between utility operators.

- Inadequate investment in grid modernization.

“The grid is only as strong as its weakest node.” — Dr. Massoud Amin, Smart Grid Pioneer

Water Supply System Failures

Contamination, pipe bursts, or pump failures can disrupt water delivery. The Flint, Michigan water crisis began with a system failure in corrosion control, leading to lead leaching into drinking water.

- Outdated infrastructure with no redundancy.

- Poor water quality monitoring.

- Delayed response to early warning signs.

Transportation Network Disruptions

From air traffic control systems to railway signaling, transportation relies on flawless coordination. In 2019, a software glitch in the UK’s air traffic control system grounded hundreds of flights.

- Legacy systems incompatible with modern upgrades.

- Single points of failure in routing algorithms.

- Insufficient failover mechanisms.

System Failure in Technology and IT

In the digital age, IT system failure can cripple businesses, leak sensitive data, or halt global services. Cloud outages, database corruption, and network failures are increasingly common.

Cloud Service Outages

Major cloud providers like AWS, Google Cloud, and Azure have experienced outages due to configuration errors, DDoS attacks, or hardware failures. In 2021, an AWS outage disrupted Netflix, Slack, and Robinhood.

- Over-reliance on a single cloud provider.

- Insufficient disaster recovery planning.

- Complex interdependencies between services.

Database Corruption and Data Loss

When databases fail, businesses lose critical information. Causes include hardware failure, software bugs, or human error during maintenance.

- Lack of regular backups or backup verification.

- Improper transaction handling leading to data inconsistency.

- Insufficient access controls exposing data to tampering.

Network Failures and Connectivity Loss

Network outages can isolate systems, prevent communication, and halt operations. In 2023, a fiber optic cable cut in the Middle East disrupted internet access across several countries.

- Physical damage to infrastructure.

- Routing table misconfigurations.

- Denial-of-service attacks overwhelming bandwidth.

Human and Organizational Factors in System Failure

Behind every technical failure, there’s often a human or organizational flaw. Culture, communication, and decision-making play critical roles in system resilience.

Siloed Communication and Lack of Transparency

When teams don’t share information, warning signs go unnoticed. The Columbia space shuttle disaster was partly due to engineers’ concerns being ignored by NASA management.

- Departmental silos preventing cross-functional collaboration.

- Suppression of dissenting opinions.

- Lack of incident reporting systems.

Poor Risk Management and Complacency

Organizations often underestimate risks, especially when systems have operated smoothly for years. This false sense of security leads to underinvestment in maintenance and training.

- Failure to conduct regular risk assessments.

- Ignoring near-misses as “non-events.”

- Overconfidence in automated systems.

Leadership Failures and Accountability Gaps

Leaders set the tone for safety and reliability. When accountability is weak, corners get cut. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill was linked to cost-cutting decisions and poor oversight by BP and its partners.

- Short-term profit prioritized over long-term safety.

- Lack of clear ownership for system integrity.

- Inadequate incident response leadership.

Cascading Failures: When One Failure Triggers Many

One of the most dangerous aspects of system failure is its potential to cascade. A small fault in one component can propagate through interconnected systems, causing widespread collapse.

Understanding Cascading System Failure

Cascading failures occur when the failure of one element increases stress on others, leading to a chain reaction. This is common in power grids, financial markets, and supply chains.

- Initial failure overloads adjacent components.

- Automated responses (like shutdowns) can accelerate the spread.

- Recovery becomes exponentially harder as more systems go offline.

“In complex systems, failure is not an exception—it’s an inevitability. The key is designing for resilience.” — Dr. Nancy Leveson, MIT Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics

Real-World Examples of Cascading Failures

The 2011 Japan earthquake and tsunami triggered a cascading failure at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant. Power loss led to cooling system failure, which caused reactor meltdowns and radiation leaks.

- 2008 Financial Crisis: Mortgage defaults triggered global banking collapse.

- 2020 Beirut Port Explosion: Poor storage of ammonium nitrate led to a blast that destroyed critical infrastructure.

- 2021 Texas Power Crisis: Cold weather caused gas well freezes, leading to power plant shutdowns and grid failure.

Preventing Cascading Failures

Prevention requires designing systems with isolation, redundancy, and graceful degradation in mind.

- Implement circuit breakers to isolate failing components.

- Use microgrids to limit the spread of power outages.

- Conduct stress tests simulating multi-point failures.

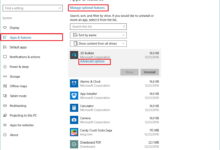

How to Prevent System Failure: Best Practices

While no system is immune to failure, smart design and proactive management can drastically reduce risk.

Implement Redundancy and Failover Mechanisms

Redundancy ensures that if one component fails, another can take over. This is standard in aviation, data centers, and medical devices.

- Use backup power supplies (UPS, generators).

- Deploy redundant servers in geographically dispersed locations.

- Design dual-path networks for critical communications.

Conduct Regular Testing and Simulations

Regular stress tests, penetration tests, and disaster recovery drills help identify weaknesses before they cause real failures.

- Perform “chaos engineering” to test system resilience (e.g., Netflix’s Chaos Monkey).

- Simulate blackouts, cyberattacks, and natural disasters.

- Review and update emergency response plans annually.

Adopt a Culture of Safety and Continuous Improvement

Organizations must foster a culture where reporting errors is encouraged, not punished. Learning from near-misses is key to preventing major failures.

- Implement blame-free incident reporting systems.

- Hold regular post-mortems after every incident.

- Invest in ongoing training and skill development.

Case Studies: Major System Failures in History

Learning from past failures is essential. Here are some of the most impactful system failures and their lessons.

The Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster (1986)

A flawed reactor design combined with operator errors during a safety test led to a catastrophic explosion. The lack of a containment structure and poor safety culture amplified the disaster.

- Lesson: Safety protocols must override operational convenience.

- Lesson: Independent oversight is critical in high-risk industries.

The Mars Climate Orbiter Loss (1999)

NASA lost a $125 million spacecraft because one team used metric units while another used imperial units. A simple unit conversion error caused the orbiter to burn up in Mars’ atmosphere.

- Lesson: Standardization is non-negotiable in complex systems.

- Lesson: Automated checks should catch basic inconsistencies.

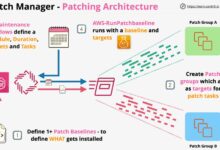

The Equifax Data Breach (2017)

A known vulnerability in Apache Struts was left unpatched, allowing hackers to steal sensitive data of 147 million people. Poor patch management and internal communication were to blame.

- Lesson: Timely software updates are a security imperative.

- Lesson: Vulnerability scanning must be continuous.

What is the most common cause of system failure?

The most common cause of system failure is human error, often compounded by poor processes, lack of training, or inadequate oversight. However, design flaws and software bugs are also leading contributors, especially in complex technological systems.

Can system failure be completely prevented?

While it’s impossible to eliminate all risks, system failure can be significantly reduced through redundancy, rigorous testing, proactive maintenance, and a strong safety culture. The goal is not perfection, but resilience—the ability to withstand and recover from failures.

What is a cascading system failure?

A cascading system failure occurs when the breakdown of one component triggers failures in interconnected systems, leading to a widespread collapse. This is common in power grids, financial networks, and IT infrastructures where dependencies are high.

How do organizations recover from system failure?

Recovery involves immediate response (containment, restoration), root cause analysis, and long-term improvements. Effective disaster recovery plans, backup systems, and clear communication are essential for minimizing downtime and rebuilding trust.

What role does AI play in preventing system failure?

AI can monitor system performance in real time, predict failures using anomaly detection, and automate responses. However, AI systems themselves can fail if not properly trained or monitored, so they must be part of a broader reliability strategy.

System failure is not just a technical issue—it’s a systemic one. Whether in infrastructure, technology, or organizations, failures reveal weaknesses in design, culture, and preparedness. By understanding the causes, learning from history, and implementing robust prevention strategies, we can build systems that are not only powerful but also resilient. The goal isn’t to avoid failure entirely—because that’s impossible—but to design systems that fail safely, recover quickly, and teach us how to do better next time.

Further Reading: